Cool Nuggets from the Financial Stability Report

In today's newsletter, we talk about the Financial Stability report and cover some interesting bits from the document.

The Story

Every 6 months the Reserve Bank of India releases a rather interesting document called the Financial Stability Report (FSR). In it, the RBI elaborates on the trends & progress in the banking system of India.

However, considering we are in the midst of a global pandemic right now, the FSR had a lot more to offer.

On Moratorium

Moratorium is a big word. It’s a complicated word. It means a suspension of some activity during a said period. And on March 27th, the Reserve Bank of India suspended all loan repayments due in March, April, and May 2020. And then, a few days later, the Reserve Bank did it once again and extended the moratorium by another three months, until August 2020.

The only problem — This assessment is inaccurate. Because the RBI didn’t suspend anything. Instead, it asked banks (nicely) to give people the option to defer loans and interest payments for three months.

It isn’t a Maafi. It isn’t a waiver. It is simply a postponement of sorts.

You’re not getting a discount on your repayments. You’re still expected to pay in full once the moratorium concludes. And monthly interest will keep accruing during the said period. But it does give you some wiggle room, especially if you don’t have the cash to keep paying your EMIs right now.

And based on the FSR, it seems most banks have let customers avail the moratorium. The report states 55% of all customers from scheduled commercial banks (like HDFC and SBI) opted to defer their loan repayments—about 50% of all outstanding loans. That’s quite a big sum.

Now bear in mind, this is data from April and it’s likely that these numbers have changed since then. However, it should still give you some idea about the whole moratorium scheme as it stands.

On Debt Levels and Emerging Market Risks

Global debt levels have reached unprecedented highs. In fact, we are more indebted today than we were back in 2008 — during the global financial crisis. Now the way we measure this is by comparing debt levels to GDP. For instance, if the country’s debt (including government, corporate and household debt) is equal to the country’s GDP, then we argue that the debt to GDP ratio is 1. If it’s higher than 1 maybe its time to exercise some caution. And right now, the global debt to GDP ratio stands at about 3.2.

So the FSR paints a grim picture on this front.

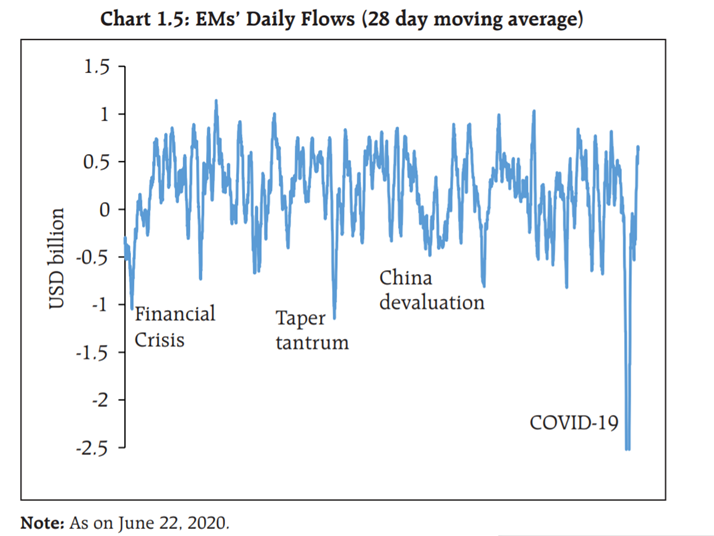

Also, foreign investors have been moving money out of emerging markets (like India) ever since COVID made landfall. This chart from the FSR ought to give you a better idea of what’s happening right now.

Whenever you see outflows like these, it’s a bad omen. Although foreign investments have been trickling in, this sort of sudden movement can cause a lot of pain. For instance, consider the Taper Tantrum incident outlined in the graph above.

Back in 2008, when the US economy was reeling from the after-effects of the global financial crisis, the country’s central bank (the US Federal Reserve) stepped up big time to prevent a sustained recession. They figured the best way to contain the mess was to flood the economy with cheap money (US Dollars), where everybody could borrow at ridiculously low-interest rates. They called it Quantitative Easing and for the most part, it worked. However, in 2013, the Federal Reserve finally indicated that it was scaling back the program and it would stop pumping indiscriminate amounts of money into the ecosystem.

This was problematic for two reasons.

- When the Fed enabled banks to borrow at such low-interest rates back in 2008, investors who were looking to turn a profit by lending money had to find another destination. After all, you can’t make a killing if you’re competing with banks that are offering interest rates close to zero.

- And so, investors started pumping their money into emerging markets in a bid to extract a higher return on their investment.

But when the US Central bank stated that it was scaling back the program, investors believed interest rates back home (in the US) would trend upwards. And when they realised they no longer needed to stay put in the emerging economies they pulled out their money overnight and we saw an outflow of foreign capital — the likes of which we hadn’t seen before.

We started losing foreign currency en masse. Investors were exchanging the local currency (Rupees) for US dollars. And with this, we saw the value of our currency erode rather quickly. The only way to stabilize the Rupee now is to start doing the same thing (in the opposite direction) — Exchange dollars for the local currency.

But you can’t do it unless you have dollars to sell in the first place. So it’s incumbent on the Reserve Bank of India to keep enough Dollar reserves just in case we might have to intervene and stabilize our currency. That’s how you prevent another Taper Tantrum crisis. And considering the FSR claims that there might be a shortage of US dollars in the next few months, you can get a sense of why the Reserve Bank has been hoarding dollars in such large numbers.

Bottom line — Anything can happen in emerging markets (including India) right now. So it’s best to be prepared.

Anyway, the FSR is a long boring document and there’s no way we will be able to cover the entire draft right now. However, we are hoping that these two use cases ought to give you a sense of the precarious financial condition plaguing our economy today.

Until next time…